Maldives has a tax issue. Good news first: according to OECD data, Maldives’ tax-to-GDP ratio, despite being 13.6 percentage points lower than the OECD average – 20.4% vs 34% – is slightly above the average of the Asia Pacific region, which in 2022 stood at 19.3%. All the biggest Southeast Asia countries did worse than the Maldives: Vietnam 19%, Philippines 18.4%, Thailand 16.7%, Malaysia 12.2%, Singapore and Indonesia 12.1%.

Furthermore, Maldives was almost able to double the tax-to-GDP ratio between 2007 and 2022: in fact, it was just 11.8% before the Financial Crisis, to reach – as we have seen – 20.4% in 2022.

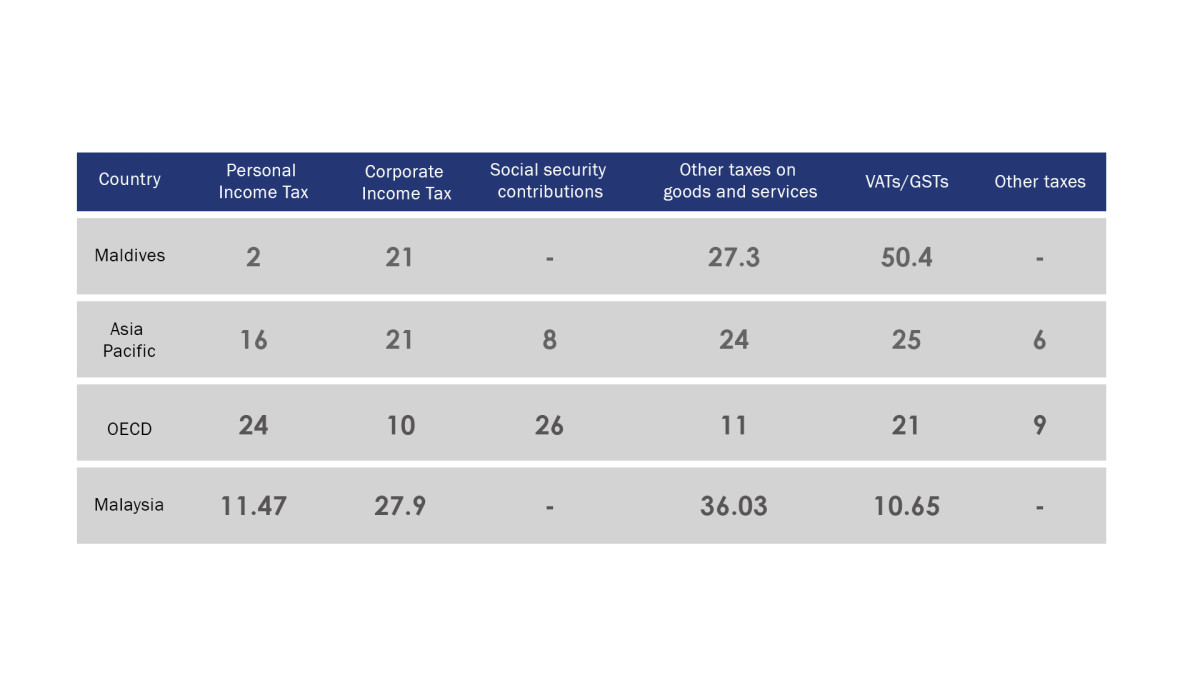

However, where problems arise is on the tax revenue composition. The highest share of tax revenues in the Maldives in 2022 was derived from value added taxes / goods and services tax (50.4%); the second-highest share of tax revenues in 2022 was derived from other taxes on goods and services (27.3%). The table below offers useful comparisons.

Tax structure, selected countries/regions (percentage of total revenues):

Even when compared to a country like Malaysia, where non-fiscal revenues play an important role, Maldives appears unable to catalyze resources through income tax, while the country relies on indirect taxation for more than three fourth of its fiscal revenues. It is true that it is difficult to draw comparisons for a country with little more than half a million citizens, but an over-reliance on indirect taxes (VAT or duties) is obviously compromising fiscal equity.

In Maldives, indirect taxation revenues are designed around a heavy system of import duties, which is not playing in favor of a population which is heavily dependent on import for its necessities: Maldives recorded a trade deficit of USD 266.70 million in August of 2024; balance of trade in Maldives averaged -139.04 USD million from 2005 until 2024, reaching a record low of -321.70 USD million in December of 2022.

Pushing on the direction of a much-needed fiscal consolidation, the government is now discussing tax hikes and subsidy rationalization; the proposed measures will affect tourism products and services, tobacco products and the green tax which is expected to double. However, negative unintended consequences are behind the corner.

Does it make sense to increase tourism-related taxes in a country where tourism directly accounts for more than 20% of the country’s GDP with a projected indirect contribution of 79% in 2022?

The new tax impact on tobacco related products, instead, is estimated to almost triple the fiscal weight on those products, without distinguishing between traditional tobacco products, alternative tobacco products and devices for the consumption of alternative products. The Maldives spends MVR 1.8 billion (USD 117 million) annually to import 400 million cigarettes. The trouble with such a measure is first given by the fact that the relative share of income destined to tobacco products is inversely related with income: the poorer the consumers – in relative terms – more the tobacco consumption. The measure, therefore, is going to weigh more on the poor in a country in which taxation already presents inequality issues being based on indirect taxes.

There is more; as the case of Malaysia amply demonstrated, excessive increases in indirect taxes on tobacco products progress together with the market share of illicit products, which in Malaysia reached almost 60%. Similar trends have been observed in other countries in the region, like Pakistan, Singapore and Hong Kong. A different approach, instead, could lead to both properly fighting tobacco addiction and increasing fiscal revenues sustainably.

Based on studies conducted by both economists and health experts, the main conclusions that a trade-off analysis applied to alternative nicotine products are:

- Heated tobacco products and e-cigarettes are better and safer alternatives for nicotine consumers, and therefore a successful harm reduction strategy is needed to acknowledge these results;

- Punitive or prohibitive laws can only spur illicit trade and therefore produce more harm for consumers’ health;

- A regulation spurring illicit trade damages legitimate businesses and reduces fiscal revenues.

Unfortunately, the newly proposed tax changes seem to go in the opposite direction, aiming at equalizing, from a fiscal perspective, all the alternative nicotine products, including the devices, with traditional tobacco products.

It should instead be recognized that electronic devices used for e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products are not tobacco products, but purely electronic devices. Therefore, the Government should classify electronic devices simply as electronic goods.

Furthermore, a taxation policy which embraces harm reduction is based on the principle of differential taxation, which means imposing product-specific taxes based on the risks that a product poses to the environment or health. In a nutshell: less harmful products should enjoy a preferential tax regime when compared to more harmful alternatives.

The first benefit produced by differential taxation is the shift in consumers’ behavior, as it produces incentives for consumers to switch to less harmful products. Secondly, a privileged treatment for alternative nicotine consumption could be a drive for innovation, as it would spur research and development investments and innovation-based solutions as well as significant changes in business models, i.e., industry transformation, precisely in favor of the less harmful alternatives: industries are incentivized to develop alternatives for products or services with negative externalities. Finally, differential taxation addresses public health as it reduces consumption of harmful products, potentially reducing the healthcare financial burden for the public healthcare providers.

With a proper fiscal system in place, shifting away from the over-reliance on indirect taxation, fiscal revenues would be boosted by the economic growth spurred by the new wave of innovations mentioned earlier.

In light of these considerations, a strong signal of a commitment to harm reduction should be the exclusion of devices from the proposed import duty increase, since these are electronic products and not tobacco products. Levying excessive import duties on the device also risks making them less affordable, thereby restricting consumers to switch to better products and disincentivizing producers to work on further innovation in these products. Similarly, alternative nicotine products should also be treated favorably from a duties-point-of-view to drive consumer switching, innovation and further investments. Finally, the duty increases on all products should be reasonable, so as to avoid tax shocks, surge in illicit trade and the related economic fallout, and instead achieve both revenue increases and public health outcomes in a sustainable manner.

In conclusion, while Maldives discusses the revision of import duties which will include tobacco products and e-cigarettes including devices, the revision should be designed in a way that takes into account the chance to commit to an effective harm reduction strategy, and as such it should be open to the principles of differential taxation and sustainability.

All this, within a realm of shifting away from the over-reliance on indirect taxation, which is burdening a community heavily dependent on imports for its basic necessities.